“Why does it matter how many [insert underrepresented group] work here? It’s about Diversity of thought, right?”

It’s a sentiment that’s holding many people and organizations back from realizing transformative success. The insidiousness of the question lies in its overlooking a major point about “diversity of thought.” Diversity of thought can only come from diversity of lived experiences. For this reason, we cannot talk about fixing the diversity problem without first addressing the systemic causes at its root. This important and critical work will shift the paradigm, empowering us to ask more thoughtful questions like: What structural inequities have kept corporate spaces so white, heteronormative and male?

When we view our commitment to and investment in diversity through this lens, we can start to really believe in our ability as change agents, not just for the sake of our businesses, but for the sake of a more equitable and inclusive future for those who are currently all but invisible in the corporate workforce. Then, we might tackle more compelling questions like: What might the impact be on society if we considered how the actions we take as leaders could address or offset these inequities in our hiring, onboarding and leadership practices?

The problem is that leaders at far too many organizations tend to treat the business case for diversity separately from that of meaning what we say when we express solidarity with underrepresented groups. As leaders, we’ve got to stop thinking about ourselves as investing in diversity programs, and start internalizing the fact that we are actually investing in people. When we remove the ROI case as the primary driver for these efforts, we unleash the power of demographic experience and cultural awareness.

But, the reality is that no single organization could fight every battle there is on the road to the inclusive future we envision, so we start with one. We look for opportunities to lift up individuals affected by these disparities in our own communities, we create inclusive spaces for them, and we support their upward mobility. Here are 3 groups and some of the conditions keeping them out of corporate workspaces and the workforce in general.

Marginalized Moms

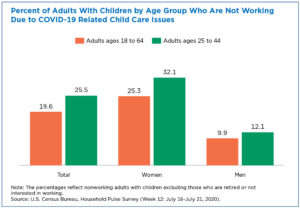

The crippling cost of childcare disproportionately affects women, often causing them to exit the workforce entirely. This has been severely exacerbated by COVID 19. In 2020, the percentage of men reporting that they had to leave their jobs due to lack of childcare was 12%. For women, that number nearly triples, at 32%.

There are many thoughtful, purpose driven organizations that approach this problem with charitable donations and outreach programs, but few, it seems, let this information be a driver to actively recruit and support women at work. And that’s a key point of understanding here: Hiring marginalized moms is not charity. It is an opportunity to impact outcomes for those women in a way that enriches society and the business by celebrating and capitalizing on their unique experiences.

Blacks left Behind: The Compounding effect of enduring systemic racism

“The unemployment rate for African Americans was at least twice as high as Caucasian unemployment for all but seven years during the 53-year period between 1962 and 2015. Research shows that more than one-third of jobs are filled through referrals, which has not changed for the last 26 years,” according to the American Bar Association.

Many brands think about these disparities in terms of avoiding scandal/brand risk or they talk in terms of the ROI benefits of a diverse team. But when we look further up the candidate funnel and really confront the root causes of the lack of Black people in the workforce, we begin to understand the deeper impact we can have as leaders of organizations.

As the following illuminates, a lack of action on this as employers, dooms us to perpetuate a status quo that supports a pretty narrow segment of the population.

“Caucasian men use their power at work to refer more Caucasian men for jobs, which disadvantages minority women. Furthermore, U.S. organizations pay out employee referral bonuses. In fact, 42 percent of U.S. organizations pay out referral bonuses, and it is even higher for the technology industry, where 58 percent provided employee bonuses for referrals. Hence, these referral policies are an example of structural racism, because the policies advantage Caucasian men (the dominant group) by increasing their access to employment and referral bonuses, while limiting minority women’s (the non-dominant group) access to employment and bonuses.”

This information handily dismantles the “ lack of diverse candidates” myth. It surfaces an important truth: Black talent exists, just not often enough in the networks of white men in power. When we approach this problem not simply from a place of “How can these candidates circumvent these obstacles?” but also “How can an organization take action against anti blackness in a way that drives positive outcomes for the black people that our PR statement says we stand with”

When considering investment in programs and training around microaggressions and unconscious bias, understand that what you are actually investing in is economic empowerment of this group by creating a healthy and inclusive culture for them to thrive at your company.

Living Out Loud LGBTQ: Enduring stigma, policies and lack of resources for LGBTQ people

In October 2020, The National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, & Medicine wrote that “Poverty and economic insecurity are more common among LGBTQI+ people. Many face lower earnings and discrimination in the workforce, as well as discrimination in housing. LGBTQI+ youth are at a greater risk of homelessness, as are transgender people of any age, particularly transgender women of color. More research is needed on the economic well-being of transgender, non-binary, and intersex people.”

Often, when we think about what LGBTQI people are up against, the emphasis is on the emotional and mental aspects of these obstacles. But in the case of work and access to opportunity, many individuals in this population are severely underserved. All this happens to the backdrop of constantly having their rights to exist in the true expression of their identity up for social and political debate.

As an organization, an ERG is great, but far less impactful if there are too few who identify as LGBTQI to really form a sense of community. Here again is an opportunity to think differently about how we engage with this population. We have to go much deeper than rainbow flags in June and truly endeavor to improve lives.

For business leaders, responsible for revenue, much of what I’ve said here may seem like wishful thinking, but I’d challenge that idea. After all, what is so bad about thinking wishfully? What would be the real risk in allowing yourself to really think big about what you can impact from your position? So, let’s take another look at what is driving our investments in DEI initiatives and rethink the questions we ask when evaluating these investments.

“What marginalized and underrepresented groups can we uplift and support through our DEI practices?” and “How might we impact society/ the community where we operate if we dared to believe ourselves capable.?” There is quite a delta between being the company that is hiring more marginalized folks for the benefit of the company, and one that does so for a higher purpose and with the express intention of uplifting communities. What if leaders stopped simply focusing on ROI when evaluating the cost of these programs and instead, focused on the opportunity their company has to meaningfully impact and offset structural inequities?